Indifference Curve Definition

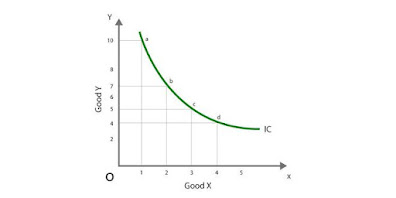

Indifference curve is a graphical

representation of a combination of products that gives a consumer a similar

level of satisfaction and renders them

indifferent. Every point on the indifference curve indicates that a person or

consumer has no preference between the two goods because they provide him with

equivalent utility.

In economics, the indifference curve investigates demand patterns for commodity combinations, budget constraints, and customer preferences. The theory applies to welfare economics and microeconomics, such as consumer and producer equilibrium, consumer surplus measurement, the theory of exchange, and so on.

Indifference Curve Assumptions

• To maximize satisfaction, the consumer is rational and makes a

transitive or consistent choice.

• The consumer is expected to purchase any combination of the

two commodities.

• Customers can rank a variety of commodities based on their

level of satisfaction. Typically, the combination with the highest level of

satisfaction is preferred.

• In the analysis, consumer behaviour remains constant.

• The utility is represented by ordinal numbers.

• Assumes that the

marginal rate of substitution will decrease.

Indifference Curve Criticisms

(1) Indifference Curves are

Non-transitive:

W.E. Armstrong is a leading critic of the indifference hypothesis, arguing that the consumer is indifferent not because he has complete knowledge of the various combinations available to him, but because of his inability to judge the difference between alternative combinations. He also believes that any two points on an indifference curve are points of indifference not because of iso-utility difference, but because of zero-utility difference.

(2) The Consumer is not

Rational:

The

utility theory, like the indifference analysis, assumes that the consumer acts

rationally. He has a calculating mind and can carry innumerable combinations of

various commodities in his head, substituting one for the other, comparing

their total utilities, and making a rational choice between various

combinations of goods. This is too much to ask of a consumer who must act

within a variety of social, economic, and legal constraints.

(3) Combinations are not based

on any Principle:

Because

the combinations are made regardless of the nature of the goods, they

frequently become absurd. How many of us buy ten pairs of shoes and eight pairs

of pants, six radios and five watches, or four scooters and three cars? Such

combinations have no relevance for the consumer.

(4) Limited Analysis of

Consumer’s Behaviour:

Furthermore, the assumption

that consumers buy more units of the same good when its price falls is

unfounded. Aside from the case of inferior goods, he may not want to have more

units of a good because he is influenced by "conspicuous consumption"

and desires to display or have variety. Changes in the consumer's tastes, as

well as his indulgence in speculative purchases, influence his preference for

the goods. Because of these exceptions, indifference analysis is a limited

study of consumer behavior.

(5) Away from Reality:

According to Prof. Robertson, "the fact

that the indifference hypothesis, the more complicated of the two

psychologically, also happens to be the more economical logically, provides no

guarantee that it is closer to the truth." He then asks if we can disregard

four-footed animals on the ground because walking only takes two feet.

Comments

Post a Comment